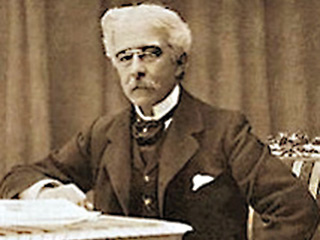

Antonio Fogazzaro

Reading Fogazzaro's novels and walking can help cultivate a sensitivity towards our surroundings, we will be able to admire the landscape as it tells its story, we will explore and rediscover its forms, we will learn not to remain indifferent, but rather, to stand in awe, and people will be drawn to an experience which is both invigorating and culturally enriching. As we succumb to the influences of literature and the landscape, our eye will be more perceptive to Beauty.

Antonio Fogazzaro was born in Vicenza in 1842 into a wealthy family who was actively involved in the struggle against the Austrian Empire. He was taught by the poet Don Giacomo Zanella, an eminent literary figure in Vicenza. In 1864, he graduated in Law at Turin and then lived in Milan where he practised as a lawyer. He married Margherita Valmarana in 1866 and three years later he moved back to Vicenza to dedicate himself to his literary career. He was a member of the Congregazione della Carità (a state-run charitable association) and of the Provincial Board of Education, and he held political positions as a local councillor and Italian senator. He was the chief Arbitrator for the Banca Popolare di Vicenza and was Chairman of the Società del Quartetto and the Accademia Olimpica.

Following his short poem Miranda and his collection of verse entitled Valsolda, his first novel, Malombra was published in 1881. However he found fame and success with his later novels, Daniele Cortis (1885), Il mistero del poeta (The Mystery of the Poet, 1888), Piccolo mondo antico (The Little World of the Past, 1896), Piccolo mondo moderno (The Man of the World, 1901). His last two novels, Il santo (The Saint, 1905), and Leila (1910), were banned by the church and put on the Index.

We can begin to build a portrait of Fogazzaro with two powerful pictures. The first is as “Cavaliere dello Spirito” (Knight of the Spirit), as he is depicted in letters to Matilde Serao, describing Fogazzaro as a writer who dealt with issues such as the crisis of the family, the need for reform in the Catholic Church, and the relation between faith, science, eros, and morality. The second is how Giovanni Papini described him, a deep-sea diver, plumbing the murky, monster-filled depths that is the human soul, given that Fogazzaro is most concerned to describe the complexities and ambiguities of the modern soul. To these pictures can be added that of the gentleman writer, a man accustomed to living in elegantly furnished, aristocratic villas, wealthy, unencumbered by the cares of a practical life, skilled in the art of observing things and souls, with a graceful hint of poetry.

My vision of the world is different from the one my fellow artists see, different from the real world. I do not see the great men that others see, but I see great women that nobody knows about. In all souls I see reflected the glow of an unknown light, a sovereign idea. I neither sell, nor break my spectacles, but rather I keep them, I have them gold-plated as a reminder of the warm and generous fire in my heart when it was deluded, but happily so, into thinking that I could use them to penetrate the universe, to glean from it, as my own idea of art told me, phantoms of eternal souls or living shadows of beings, as a reminder of some faithful, burning spirit.

And again Fogazzaro wrote about himself and his experience as a writer:

My books are drawn in part from other books, in part from the truth in things, and in part from the depths of my own soul; because my soul, too, is a sky filled with shadows and stars which rise and set and rise again without rest, and therein lies an abyss so deep that not even the inner eye can penetrate it.

Here, Fogazzaro provides us with the sources for his works: other authors' books, the “truth” in his surroundings, his experience, and contemporary religious and political characters, but especially the “truth” in his exploration of feelings and our destiny as humans. Fogazzaro explores his own soul, fraught by the tensions between virtue and passion, but also driven by Christian evolutionary theory, by his own political commitment and by spiritual pantheism.

Other aspects of Fogazzaro's personality can be gleaned from the comments of another writer from Vicenza: in an article written in 1942, Guido Piovene cleverly draws remarkable analogies between Fogazzaro's character and the contours of his landscape:

He shied away from things which were too well-defined, from the harsh lines of residential areas; Vicenza and its surrounding landscape, so softly nuanced, so fleeting and elusive, made up of so many individual elements which nevertheless defied an overall definition, was perfectly suited to his temperament. The landscape is a collage where the languor of Venice or blessed skies across the plains, laden with the scent of the sea, perhaps even the East, lie within close range of the crested Dolomites and the vast valleys beneath them. All this pleased Fogazzaro, it suited his uncertain spirit, always aspiring to something higher, swaying between a host of often conflicting fantasies, and for each of them he would seek out the soothing embrace of both the meadows,and the woods, and the mountains. Yet he also enjoyed life in the villas, as nowhere else had the art of sojourning in villas reached such unparalleled levels of perfection. One of the most frequently occurring landscape images in his art is the joy that could be felt before a bare peak, sheer rock, soaring upwards like a cry renting the silence, yet bursting forth from the lush greenery, the sensual and blossoming life in the woods and meadows. One might say that he disdained the conquered heights of the mountains preferring to view them from below, when they still appeared to him as something to aspire to, a fairytale, a fantastical place, in a sense the ideal of an unfulfilled spiritual life.

In Fogazzaro's novels the landscape is not a static element but behaves as though it were alive, underlining the shifting feelings of the characters, it makes its entrance like an “actor” and reacts with “prompts”.

We can add further colour to the portrait of the novelist with fragments relating to Fogazzaro the “geographer” and “botanist”. These aspects may well draw readers to his novels as Fogazzaro was not only a careful observer of the human soul, but a lover of Nature.

From the great slopes of our mountains to our poetic sea shores, nature has lavished on us so many scenes of incomparable beauty that we may imagine any kind of scene set there, from the most grim to the most hilarious! […] only a very few observe our natural surroundings.

Fogazzaro was a “geographer” and “botanist” because he expressed that love for the landscape, for plants and flowers, which is bound to everyday experience and charged with memories. The places he described were not merely a backdrop but places he knew and loved, a collection of clearly identifiable places in Montegalda, Vicenza and Val d'Astico, and like all good geographers he measured space in a very simple way – by walking. It is a recurring theme in his novels and the moment when the characters reveal their deepest emotions, be it curiosity, fear, enthusiasm or even passion.

Fogazzaro the geographer discovers that “little” world of serenity embedded in his native land, not by means of a quiet life, but through familiar gestures, through sacrifice and pain. However, his little world is riven by the anxiety of the soul and the precarious nature of human relationships.

Fogazzaro's originality lies in his interpretation: in his novels the landscape is not cold and impersonal but a living being who is transformed and alive, it interacts with the anguished events surrounding the characters, it is both mirror and interlocutor, it conveys messages and approval, it is the confidante of the hidden truths in the characters' souls. Lovingly, Fogazzaro re-evokes the places of his trembling and suffering soul, his refined gaze lingers there tenderly, and the reader is invited to inhabit this space and partake in his “little” world. However, while the city is a place of mystery and solitude in this world, the ideal place to live is the countryside where one can aspire to live peacefully, sheltered from all care and worry in an enchanted place (suited, as Piovene said, to Fogazzaro's “uncertain” soul “aspirating to something higher”).

There is still another element to help discover Fogazzaro's soul and his geography, and this is nature. The author uses the same sentiments to bring his characters to life as he does to bring nature to life. Its evocative presence takes on a multitude of forms – voices, sound, light, shade – its world comes alive, unleashing a transformation where it becomes, to all intents and purposes, an extension of the characters' state of mind.

There is a cast of voices and sounds acting on that blurred area that lies between the soul and the senses: they come from the mountains in moments of solitude or meditation, the sounds of the lake accompany grave or mysterious thoughts, the river rumbles its presence, the rain cries, and the wind moans in anxiety or symbolises the purity of the landscape; but also a well-tended garden, the flowers, chastely pure or sensuously intoxicating and certain types of trees add a climate of intimacy and mirror the characters' inner world.

For those interested in reading Fogazzaro's novels and discovering the connections between his works and the places they are set in the Vicenza area, there follow selected excerpts from Daniele Cortis, Piccolo mondo moderno (The Man of the World) and Leila, which show how the characters' moods are mirrored in the landscape.

Daniele Cortis

Elena, "pale and perplexed", is walking alone in the grounds of Villa Cortis, which is actually Villa Velo in Velo d'Astico. There is a subdued, fleeting atmosphere in the woods. The shadows have a physical presence, shrouding the woman's thoughts and disorienting her. Like real actors they nudge her towards the message, “the poem of life and shadow”, testament to a sublime and other-worldly love: “In winter, and in summer, from near and from far, as long as I live, and beyond that again”. The intertwined branches of the acacias and the clasped hands on the base of the column are symbols of a desire which is, as yet, unfulfilled.

She saw the wall surrounding the French garden, and above it the gleaming fountain and the dark-wooded sides of the hills. With pale and sad countenance she went up to the little grass lawn in front of the house, passed through the court-yard, and turning off by the garden railings, disappeared in the wood. She lost herself in the mystery of the shadows which cast around their silent invitation, and which in a short time became thick and dense, lying darkly over the paths that wind in and out among them. Within those woods are hills and valleys perpetually shaded; lakes, ponds, and glades girt round by overshadowing trees, and there may be heard, too, the voices of invisible springs. The branches of the lofty trees, growing around the garden gate, by their waving and murmuring in the wind, suggest a poem of shadow and of life, and give one a foretaste of its magnificence.

She descended into the valley which opened on her left immediately after this turning, a narrow valley through which a stream covered with water-lilies trickled; the grass grew thickly over the path, and overhead the branches of the acacias on either side mingled, and cast a golden green shadow. Thence she mounted to a quiet opening in the hills, and there, among the trees on a grassy plateau, stood a column of ancient marble, brought from the baths of Caracalla to this other solitude, and bearing on its base two clasped hands carved in relief, and the following words:

HYEME ET AESTATE ET PROPE ET PROCUL USQUE DUM VIVAM ET ULTRA

Elena reappeared half-an-hour later still paler. She closed the garden gate behind her, leaning her head against it for a last look at the dear flowers, and to say to them, “Shall I ever see you again?” The trees could not hear her, they were too high, but they still swayed and murmured in the wind, offering her the poem of life and shadow, the sweet day-dreams of love.

The river announces its presence through sound as Daniele returns to Villascura, in reality Velo d'Astico, in his carriage. He is weary and his thoughts race ahead like the river currents themselves.

He felt ill at ease, and disturbed; disgusted with himself, with politics, with his obstinate enemies and his stupid friends, with the anger he showed to some and the toleration he showed to the others. Italy! Yes, but if he did not succeed to-day, he would to-morrow. It was his destiny, and his determination; but what he would not give for one day of love! To forget everything for one day, to contemn the world, and to unite her the most beautiful to him the most powerful! Visions of intense happiness passed before him. From the road which, passing straight through the plane trees, on the border of an immense plateau watered by the blue streams from the Alps, the eyes of Cortis greedily sought the shadowy clouds which hung on the edge of the mountains. He could see Elena and himself hidden in a house amongst those deserted wilds. Now he felt her arms, fresh and gentle as those streams, encircling him.

In this scene, natural elements, including the mountains, bear witness with their presence, they dominate the scene, sealing a solemn promise:

Her mind is already yours; she shall be yours in the next world. Now that she is going, do you go forth also, tempered by sadness; go forth, fight, suffer, be amongst men, a noble instrument of truth and justice; the stars, the mountains, the grave old fir-trees, all bore witness to his answer, and heard him say, – 'Yes, it shall be so!'

Fogazzaro shows his passion for botany as he describes certain types of plants which are typically found where his novels are set. Fir trees are a recurring theme in Daniele Cortis, providing a backdrop as the two main characters stroll together, but also symbolising sadness and strength as they relate with the human state of mind. The firs dominate the landscape as Daniele walks with Elena in "Villa Carrè", namely Villa Valmarana Ciscato in Seghe di Velo d'Astico:

They reached in silence an open space , whence one path ran to the right, across the fields, towards Villascura and Cortis's house; another sloped away to the left towards the torrent of Rovese, opposite to the naked, overhanging boulders of Monte Barco; and a third ran straight to the three tall firs, which overlooked the valley, from the edge of a steep declivity. He went straight on towards the fir-trees.

And a little further on:

At length they reached the firs, which were groaning overhead, blown about by the wind, and which showered down large drops of rain.

However, the “old, sad fir-tree” symbolises Elena's destiny, as she is pressurised by her husband:

The porch formed a sort of telescope, and away beyond the fir-trees the sky showed a pale greenish hue, while it was turquoise over the plain. Elena went out without any umbrella, walking up to the old fir-tree with drooping branches, which has now disappeared, having yielded, after centuries, to a storm, as if to verify the sad dream of its young mistress whom it never saw again. Elena laid her hand for a moment on its huge, faithful trunk, and turned away.

Piccolo mondo moderno [The Man of the World]

Piero has the moral weakness typical of Fogazzaro's male characters, but he is destined to be called to his vocation. Jeanne is a temptress, troubled and sceptical. The reader is left feeling that perhaps she is sincere in her behaviour, seeking the elevation of the soul rather than mere perversion. They are at once attracted and repulsed by their love for each other. Here again, natural elements intervene and interact with the characters. For example, in the grounds of Villa Fogazzaro Roi Colbachini ("Villa Flores" in Piccolo mondo moderno) in Montegalda, when Don Giuseppe, Piero Maironi's confessor, meets Piero's mother-in-law, the “sorrowing and weary” Marchesa Scremin, the garden is protagonist, the ideal place for their silent communication:

A grouping of clear notes around the calm movement of a slow melody, neither gay nor sad, would alone have the power to express that intangible inward something that escapes the poet when he seeks to describe the slow progress of Don Giuseppe and the Marchesa among the grasses swaying in the wind beneath the flickering shadows of the silvery clouds, among the bushes the whispering of whose leaves was interrupted by the sad, persistent notes and soaring runs of nightingales. The couple exchanged hardly a word, and therefore only music could describe this silence so full of meaning, this not unconscious communing of their souls, a communing expressive of mutual pity; the Marchesa reflecting how the old priest, cherishing a gentle, poetic hope, had prepared these beautiful surroundings for his dear ones, now, alas, all descended to the grave; Don Giuseppe reflecting upon the kindness of this sorrowing, weary woman, who, to please him, was exhibiting such an interest in his garden; the hearts of both were soothed, meanwhile, by that most lasting of earth's pleasures, a calm appreciation of the beautiful.

And then there are the flowers: in the moonlit garden of "Villa Diedo", namely Villa Valmarana ai Nani in Vicenza, the restless roses sway seductively, intensely mirroring Piero's quivering passion. They echo the young man, leading Jeanne towards temptation as she stands clothed in the same white as the terrace, a symbol of purity, igniting forbidden desires:

Jeanne was standing behind the balustrade, a small, white cape thrown over her shoulders. “This is good of you!” she said in answer to his respectful salutation. Hat in hand, Piero went up to the terrace with a smile upon his face that was too much like the smile of the woman who was advancing to meet him. It was indeed magnificent in the moonlight, this white marble terrace, jutting out from the first floor of the villa with its flight of broad steps leading down into the garden, its balustrade which the creeping roses had taken by storm and hidden beneath a tangled glory of dense foliage and great flesh-coloured eyes, long branches swaying in the vagrant breezes of the night. It was magnificent with its surrounding circle of beauty, sweeping from the dark and humble plains on the North to the radiant brightness in the sky above the lighted city. “Why not stay here?” Piero said in an undertone as if the innocent words might betray to some inquisitive ear his longing for an hour of delight in that solitary and enchanted spot among the restless roses, which rustled a voluptuous invitation.

And again the roses in "Villa Diedo" (Villa Valmarana ai Nani in Vicenza), murmuring voices alternating between torment and passion:

Only a thin, silver rim of the moon reddish globe was still shining when they once more ascended the dark terrace. In the restless air, the swaying of the roses, indistinctly heard, sounded like the voices of desire and pain. The sprays seen but indistinctly, waving from side to side, seemed like the arms of staggering blind men. As he leaned forward to turn the reclining-chair towards the west, where the moon was setting, Piero brushed Jeanne's shoulder with his lips.

Then we come to Vena di Fonte Alta, which is, in fact, Tonezza del Cimone. The fog acts to isolate Jeanne from the earthly world, nudging her gently into a world of purity. It resonates with her heart-felt desire for a life together with Piero, but it also forebodes that their union will only be a spiritual one.

A veil had fallen on the emerald of the fields; the shadows of the trees had vanished in the diffused light of the sun that was concealed; the dense fog that had come smoking up from the valleys was invading all the upper hollows of Vena and the tops of the forests, deadening the sound of the scattered cow-bells in the pastures, enveloping and darkening the slopes of Picco Astore. It seemed to Jeanne that a damp white cloak was descending upon the soft fields, was enwrapping Piero and herself in its woolly folds, was cutting them off from the world of human anxieties, from the past and from the present, and filling them with a sweet sense that they were souls of another planet. She realized that an hour of supreme importance was approaching, that there hung in the balance not only her own fate and happiness – what did they matter, after all? – but the happiness also of the man she loved, the man who was being led astray by fatal dreams. Timidly she passed her hand through his arm, whispering: “Do you mind?” And although his “No” had a cold ring she pressed her lovely form to his side. “Dearest!” she murmured.

After this decisive moment, the inebriating fog again returns, but then lifts to reveal the soaring mountains centre stage, and these very mountains seem to confirm Jeanne's foreboding that earthly love for Piero will be impossible:

And slowly, very slowly, the young man's face did indeed approach hers, which was composing itself slowly, very slowly, and was lifting itself gravely towards the meeting. Then their two souls that had risen to their lips uttered a thing so wonderful that when their lips parted at last, their eyes could not bear each other's gaze. It was not the first time Piero and Jeanne had met in that unspoken thought, but they had always met with hostility. Now it was no longer so. Now the woman knew that there was one repugnant way of binding her lover for ever; the man knew that there was one sweet way of riveting his chains for ever, and he saw that her resistance was shaken. Both, at once attracted and repulsed, trembled with emotion. Meanwhile an unpleasant wind had sprung up and was blowing the fog into their faces. Jeanne and Piero started towards Rio Freddo, she leading the way in silence, conscious of his eyes fixed upon her, and turning her head to smile at him when that gaze became so piercing she could not bear it. Little by little the fog lifted, and on the left there loomed, black and towering, the tragic Picco Astòre.

We conclude this series of images with the mountains: Vena di Fonte Alta is in fact Tonezza del Cimone, “five hours from the city, two hours of train and three by carriage; it lay one thousand metres above the level of the sea, and offered the attractions of pine-forests, beech-groves solitude and quiet”. Fogazzaro first describes it almost as an animal, but then softens and and we sense a loving familiarity with the place.

The spur that bears Vena di Fonte Alta stretches forward from the base of Picco Astore, its twin horns facing the great stone quarry of Villascura. Towering above the abyss that encircles them, the pine forests and beech groves of Vena wave against a background of sky, spotted here and there with pale emerald, where the fields press them asunder and overflow, and dotted with red and white where small houses are huddled together in groups. He who contemplates them from the top of the sloping and soaring Picco Astore, or of the lofty, cloud-capped mountains of Val di Rovese and of Val di Posina, may not realize their delicate and exquisite poetry. But the wayfarer who threads their winding depths asks himself if, when the world was young, this was not the scene of the short loves of sad spirits of the hills and of gay spirits of the air; if the earth, in obedience to their varying moods, did not transform itself around them again and again, now forming shady marriage-beds or leafy couches for reposeful contemplation, now surrounding them with scenes of melancholy or of mirth, of great thought or of merry jest; which changes ceasing when the lovers suddenly vanished, the earth retained for evermore the form it had last assumed. Every object bears the impress of a sentiment.

As his wife's health worsens, Piero leaves Vena and the panorama rushes past. The landscape is described in all its aspects, it holds so many secrets, and Piero dwells on his thoughts, examining his conscience as the old horse trots rhythmically, arousing forebodings and dreary expectations.

Down, down into the darkness he went behind the slow-trotting, jaded horse, perched on the crazy cart beside a mute companion. Above him the woods, the pastures with their paths, the thickets, the fountains that knew so much of his secret, and Picco Astore itself were vanishing for ever. Down, down beneath the glistening stars, now following a bare slope, now passing black groups of narrow cabins. Above him the house where Jeanne, all unconscious, lay sleeping is vanishing for ever. Down, down behind the jaded, slow-trotting horse, through a grove of sleeping beeches, the vanguard of a few firs that are awake and watching, and along the curving brink of precipices. Down, down with the haunting horror of the betrayal he, in his selfishness, had been planning. Down, down from the cold winds of the heights into an atmosphere that grew ever more stifling, with the vision of his whole sad life.

Leila

This is Fogazzaro's last novel, set in Velo d'Astico. The main character, Massimo (based on his friend and follower Tommaso Gallarati Scotti) has traits of incoherence and restlessness, while Leila (based on his friend Agnes Blanck) although young, shows signs of pride and repressed sensuality. Leila is not only proud but also courageous, resourceful and two-sided: she sometimes appears like an impenetrable Sphinx while at other times she is a sweet defenceless creature. However she turns out to be the only character in Fogazzaro's novels who symbolises, as a future bride, the Catholic ideal of family.

From Elena's silent sacrifice, to Daniele and Piero's mission and Leila's announcement of marriage as a continuation of life, Fogazzaro never fails to engage his reader on a journey which is marked by anguish, pain and sacrifice, and yet is always striving higher towards a more noble destiny, towards a greater Good.

In Leila, when Massimo's train arrives in Velo d'Astico from Milan, he is restored by the view of the mountains:

The delicately arched brow of Torraro divided the space that yawned between Priaforà and Caviogio, whose black and might outlines swept downwards majestically, like the flowing robes of giant monarchs. His thirsting soul found comfort in the brooding peace of the scene.

The mountains heighten Massimo's heady state caused by love:

Leila had suddenly sat down at the piano and played Schumann's “Aveu”. He had followed the music with keen delight, gazing upwards through the opening in the gallery at a slender, dolomitic peak, swathed in the blue mists like the tremulous outline of a dream. And now, within the little church, he was trying to recall that indescribable moment, that sweet music, and the mountain peak, cleaving the blue ether like a shaft of passion shot skyward.

Leila is attracted by the voice of the stream near La Montanina (Fogazzaro's villa in Velo d'Astico) as, in a moment of night-time folly, the young woman sinks into the water as if to cleanse herself of her thoughts about Massimo.

She turned left, knowing of a path that led from the avenue to some acacia-trees by the rivulet, the same rivulet that splashes and sings farther on. She found the path and paused among the acacias on the bank of the stream, which she could hear but not see. Instinctively she began to undress herself, at the invitation of that soft voice, then, awaking to a sense of her actions, she dipped her hand in the water. It was cold. All the better; it would do her the more good. And she went on undressing, never heeding where she flung her garments, removing them all except the last. She put her foot into the running water and shivered. She tested the bottom – pebbles beneath a couple of feet of water. She put her other foot in and, her heart gripped by the chill, let herself sink slowly into the water with closed eyes and parted lips, uttering little sighs the while. The water covered her with icy caresses and rippled gently about her neck and heaving bosom. Other sweet voices sounded in the air. Leila opened her eyes and raised herself in amazement. She seemed clothed in light, which shone upon the trembling waters and wrapped the bank and her clothes lying beneath the swaying, whispering trees in a silver radiance. It was the rising of the moon, a mysterious awakening of all things in the dead of night. Flowers were raining from the acacias upon the stream and its banks. The girl pressed her folded arms against her breast, and, under the gathering moonlight, amidst the odours of the woods and the rain of the flowers, some indefinable emotion filled her heart with welling tears, which fell hot and silent into the quivering water. Presently she climbed the bank, dressed herself as best she could, and then, with throbbing heart, fled back along the same path, like a castaway who suddenly finds himself safe.

The trees prompt her tyrannically but then tenderly comfort Leila's troubled thoughts:

Through the open verandah she passed into the garden, trying to fix her mind on Don Aurelio's flight. But the very trees she passed seemed to be reminding her of those thoughts from which she shrank. She began walking faster to escape their silent scrutiny, but on the up-hill road, where she was obliged to go more slowly, the great, spreading chestnut-trees renewed the tyranny and hung over her in compassionate lament, murmuring: "Poor girl! You refused Massimo's love when others said yes. Now that Signor Marcello also refuses, you no longer have the strength, you would say yes but there is no one to ask you any more, poor, poor, poor girl!"

Then comes the wind: it accompanies Leila as she anxiously reads Massimo's letter to Donna Fedele and thrills to learn that the young man has spoken of her with great feeling:

Leaving the road, Leila climbed upwards on her left among the blossoming rhododendrons. She seated herself there, the only living figure in this great windy desert, and began mechanically to pick the flowers on each side of her. She heaped them in her lap and held them in her hands, and for a long time let her eyes and thoughts rest quietly upon them. Then, with as much composure as she could muster, she brought out the letter, restrained her desire to glance through it in search of her own name, and proceeded to read it slowly from beginning to end. A cloud came in front of her eyes, and she felt herself as a helpless atom in the presence of a compelling fate. Leila turned once again to Massimo's passionate words, reading and kissing them again and again. At last she put away the letter with a long sigh of contentment. As one who had finally reached the end of a long and arduous journey. A tremendous sense of physical well-being seized her; and she stood up and stretched out her arms as if to embrace a wonderful new world that had been given her. She embraced the cold wind as it blew against her face, she embraced the wild mountain scenery before her, their slopes glowing pink in the setting sun, and she embraced the swaying rhododendrons around her.

And finally the flowers: the petals and the scent of the flowers in the garden at La Montanina have tenderly beguile Leila with their words:

Leila had filled her room for the night with roses, honeysuckle and acacia. It was a weakness of hers. She had as many flowers as possible brought to her room, and she delighted in the strongest scents. That night she had a sea of flowers. She stuck several bunches of acacia between the bed-head and the wall, and a bunch of roses between the wall and a holy picture. She loved to lie in bed and feel the petals falling on her face. She put out the light, turned upon her side, indulging her consciousness of fragrance as if she were listening to some caressing language.